Lin Shaoyang developed a passion for classical Chinese literature early in life. Yet at 15, he chose to study Japanese at university—a decision that set him on a lasting journey into East Asian culture and history. Now a Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Macau (UM), Prof Lin focuses his research on the concept of ‘wen’ (文), a fundamental cultural notion within the East Asian Sinitic sphere. He examines the reasons behind the decline, even disappearance, of ‘wen’ in modern times and considers its significance in today’s globalised world.

From Chinese classics to the Sinitic sphere

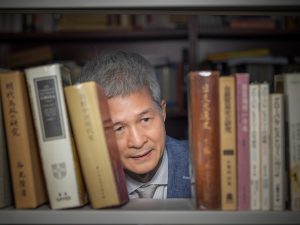

With ancestral roots in Zijin County, Guangdong Province, Prof Lin’s academic journey began with the education he received at home. In his UM office where the shelves are packed with over a thousand volumes in Chinese, Japanese, and English, Prof Lin reflects, ‘My parents were both secondary school teachers. They had an exceptional ability to recognise potential in their students and encouraged me to pursue the humanities from an early age.’

In 1977, the National College Entrance Examination (gaokao) was reinstated in mainland China. Prof Lin took the exam in 1979 at the age of 15. Shortly before the exam day, he came across a Chinese-Japanese dictionary. ‘I noticed the use of Chinese characters, which are known as “kanji”, in the Japanese language and became very curious about it. This curiosity sparked my interest in studying Japan. China and Japan are both part of the Sinitic sphere, sharing a cultural foundation yet remaining distinct. I began to wonder: beyond the conflicts we often heard about, what other connections existed between the two nations throughout history?’ This question led him to begin learning Japanese, intertwining his curiosity about Japan with reflections on China. ‘I view East Asia as a unified sphere. My research about China and Japan has always begun from an East Asian framework that transcends national borders. Of course, this East Asia is also situated within the broader context of global history,’ Prof Lin explains.

An academic journey from Xiamen to Tokyo

Prof Lin went on to study in the Department of Foreign Languages at Xiamen University (formerly called Amoy University), where he was taught by Hideo Mori, a University of Tsukuba graduate and scholar of pre-Qin Chinese philosophy. The late Prof Mori was dedicated to teaching. He invited Prof Lin and a few other top students to participate in discussions at his home every week, giving them an early taste of master’s-level academic training in their fourth year of undergraduate studies. ‘I had been sceptical of the rigid structure of academic disciplines during my university years. Driven by intense curiosity, I learned Japanese within a year or two. With Prof Mori’s guidance, I began exploring East Asian history and culture in my third and fourth years, without being affected by the constraints of conventional academic boundaries. My rapid academic progress owes much to Prof Mori’s mentorship, for which I remain grateful to this day.’

By this time, Prof Lin had been committed to pursuing an academic career. He went on to pursue a master’s degree at Jilin University. While his roommate was in the Philosophy Department and Prof Lin was studying literature, he felt increasingly sceptical of the rigid boundaries within ‘literature’ as a discipline. His interests spanned literature, history, and philosophy, with his research taking on an intellectual history focus.

Exploring the intellectual history of Japan

Prof Lin furthered his education at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo (UTokyo), where he later taught for many years. ‘Post-war Japanese society was profoundly affected by American culture, yet intellectuals looked to French and German thought, viewing America’s influence as embedded within Japan’s own state power structure,’ he reflects. His mentor, Prof Yoichi Komori, was one of these intellectuals. A leading figure among Japan’s anti-establishment thinkers, Prof Komori adopted a broad view of ‘literature’ as a lens through which to study Japan’s modern history. Prof Lin recalls the frequent in-depth discussions with prominent Japanese intellectuals like Komori during his years studying and teaching in Japan. For an intellectual historian, he notes, this experience was akin to anthropological fieldwork—an invaluable asset for his research. ‘The discussions also inspired me to explore the relationship between “wen” in East Asian traditions and intellectual life.’ Prof Lin regards ‘wen’ as a kind of ‘religion’ without God for intellectuals in the Sinitic sphere, and his research on Japanese thought focuses on the late 17th to early 18th-century Edo period and post-war 20th-century Japan.

Wen: An encompassing concept

Prof Lin describes himself as a typical scholar of modern intellectual history, although his definition of ‘modern’ starts in the late 16th century, in contrast to the conventional interpretation. His fascination with the East Asian concept of ‘wen’ dates back to his early academic years, initially sparked by his perplexity over its decline in the modern era—a focus of his doctoral dissertation. ‘The concept of “wen” traces back to the pre-Qin era. For example, The Analects is rich with discussions of “wen”, covering what we would now refer to as literature, history, philosophy, and language. The early 6th-century work Wen Xin Diao Long (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons) even described the natural world—mountains, rivers, flora, and fauna—as expressions of “wen”, a far broader idea than the “literature” concept in English, which focuses mainly on novels,’ Prof Lin explains. ‘From a young age, I resisted rigid disciplinary boundaries, and this perspective directly influenced my early academic path and subsequent development.’ Over time, Prof Lin observed that ‘wen’ is an intricate concept in the Chinese tradition, encompassing politics, morality, and even cosmic order, which makes it challenging to define. In diplomacy, for example, ‘wen’ often manifests through Confucian language, emphasising moral governance and civil rule, presented as a China-centred model of security balance. The Chinese tributary rituals and the order they establish exemplify this system. However, when this order broke down, the problem of war, or ‘wu’ (武, meaning military force), emerged. In view of this, Prof Lin, in recent years, has expanded his research to examine the East Asian tributary system of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, exploring the conflicts that arose as the order of ‘wen’ began to disintegrate.

Prof Lin believes that scholars answer questions rather than studying a specific academic discipline. Therefore, scholars should not confine themselves to strict disciplinary boundaries. ‘We are guided by questions as we explore a field, so we should be open to seeking answers from other disciplines when necessary. For example, while researching the relationship between East Asian tributary rituals and “wen”, I’ve found that traditional historical studies alone could not fully address my questions. I needed to draw on methods and theories from social sciences, including anthropology, religious studies on rituals, and sociology, to arrive at more convincing answers.’

Two decades devoted to Zhang Taiyan’s thought

While studying and working at UTokyo, Prof Lin began exploring the relationship between ‘wen’ and the ideas of prominent European thinkers influential in Japan at that time, including German hermeneutic philosophers and French intellectuals such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida. This inquiry offered him a fresh perspective for reimagining ‘wen’. Moreover, Prof Lin believes that there was a thinker in East Asia who rivalled these Western figures intellectually, but with a more politically remarkable background and close connections to Japan. This thinker was Zhang Taiyan (1869–1936) from China, who is often remembered alongside Sun Yat-sen and Huang Xing as one of the ‘Three Revolutionaries’ in the late Qing Dynasty.

Prof Lin notes that Zhang Taiyan had a profound understanding of the power of ‘wen’. During the revolutionary era in the late Qing Dynasty, while Sun Yat-sen led the strategic vision of the Tongmenghui alliance, Zhang advanced the anti-Qing revolution and the establishment of the Republic of China through his ideas and writings. He also called for solidarity among revolutionaries across Asia to liberate those oppressed by imperialism and authoritarianism. These ideals had a significant impact on Third World discourses, particularly on the narrative of ‘small nations’ resisting dominant powers.

In 2004, Prof Lin completed his doctoral studies at UTokyo and was soon appointed as an assistant professor in the university’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, later rising to the rank of Full Professor. He also taught at the City University of Hong Kong for two periods due to family reasons. Over the past two decades, Prof Lin has been dedicated to his research on Zhang Taiyan and the concept of revolution through ‘wen’—a form of revolution distinct from narrowly-defined violent movements. His work has made a significant impact in the field. In 2004, his book The Conflict of Wen in Japanese Modernity was included on the annual booklist at Beijing’s All Sages Bookstore. The book drew significant attention because it reintroduced ‘wen’—an idea largely forgotten over time—as a theoretical concept and engaged it in dialogue with Western thought. This work was a by-product of his doctoral dissertation. Prof Lin’s research has also garnered considerable interest in Japan, similarly because it has revived ‘wen’ as an intellectual and theoretical concept long overlooked. In 2009, he published his Japanese-language book, Rhetoric and Thought: Zhang Taiyan and His Theory. His 2018 Chinese-language work, Revolution by Means of Culture: The Late Qing Revolution and Zhang Taiyan from 1900 to 1911, focuses on Zhang Taiyan’s ideas, examining how the late Qing revolution employed ‘wen’ as a transformative tool. This interpretation offers a unique perspective on late Qing revolutionary and intellectual history, presenting a fresh view distinct from traditional accounts of the 1911 Revolution (Xinhai Revolution).

Exploring Macao and East Asian history in the context of globalisation

In 2022, Prof Lin joined the UM’s Department of History as a Distinguished Professor and took on the role of Head of Academic Programmes and Publications at the UM Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, where he serves as editor-in-chief of South China Quarterly: Journal of University of Macau. ‘Macao has a connection to my research,’ he explains. ‘In recent years, I have been studying the wars from 1592 to early 1599, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi attempted to invade China in the Ming Dynasty through Korea. This historical episode was intricately connected with Macao. Without the interactions between emerging global trade networks following Europe’s Age of Exploration and the Ming Dynasty’s policy of integrating tribute with trade, the dynamic networks of international commerce would not have developed as they did. And without this backdrop, new urban centres like Amoy (Xiamen) and Macao would not have emerged.’ Prof Lin adds, ‘Macao served as a pivotal hub in global trade networks from the 16th century onwards, directly linking Japan’s Nagasaki with the Philippines, which was then a Spanish colony. Macao also indirectly connected Europe and the Americas. The role of Macao is not only crucial for understanding Chinese history from the 16th century onwards, but also indispensable for studying the history of Japan in the 16th and 17th centuries.’

Prof Lin also examines the manifestation of ‘wen’ in international relations since the 16th century, and explores conflicts arising from the breakdown of orders grounded in ‘wen’, thereby tracing the evolution of ‘wen’ within the context of globalisation. He adds, ‘I am writing a book on Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s attempted invasion of Korea as a route to attack the Ming Dynasty. The research process involves consulting Chinese and Portuguese-language literature preserved in Macao.’

Reimagining a transnational East Asian tradition

After moving to Macao, Prof Lin published his book Postwar and Postmodern Japan: Its Continuities and Discontinuities in August 2023. This is the first work in Chinese, Japanese, or English-language academia that systematically examines the relationship between Japanese intellectual thought after World War II and postmodernism. He is currently adapting the book into an English edition, with plans for a Chinese version to follow. Given the complex nature of Zhang Taiyan’s works, Prof Lin also aims to translate and adapt his research on Zhang into an English monograph, with the goal of introducing this influential thinker to Western scholars.

As global history research continues to flourish, Prof Lin explains that he has long explored the relationship between East Asia’s concept of ‘wen’ and European thought from a global historical perspective. ‘I see myself as a scholar of comparative East Asian studies who aims to understand China and its neighbouring regions through a comparative lens. The deeper my research goes, the more I realise that solely replying on a nation-state framework to interpret China is narrow—even unacademic. Much like the Literary Chinese language, pre-Qin culture was a shared tradition across East Asia, yet this tradition was profoundly shaped by early globalisation since the 16th century. I hope to continue examining the significance of “wen” and to situate the traditional values of East Asian culture within today’s globalised world.’

Chinese & English Text / Davis Ip

Photo / Jack Ho

Source: UMagazine ISSUE 30