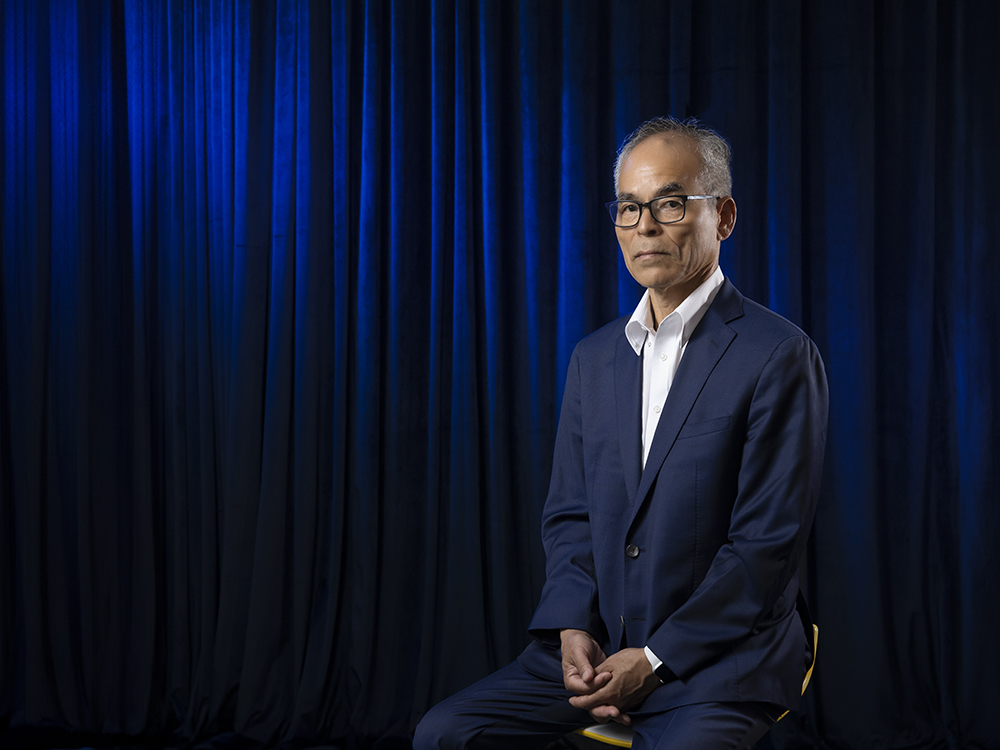

‘Doing research is similar to gambling. When everybody does it this way, you do it that way. There are always hidden paths off the main road.’ This is the motto of Prof Shuji Nakamura, who was awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics for his invention of the blue light-emitting diode (LED). He also received the Doctor of Science honoris causa degree from the University of Macau (UM) in 2020. Throughout his research career, Prof Nakamura has taken others’ sarcasm and disregard as a powerful motivation to work on new inventions. ‘Don’t give up, even when others call you a fool. Stay true to your innovative ideas,’ he said.

New materials help enhances people’s sense of well-being

Prof Nakamura first visited UM in 2016, when he attended the International Workshop on Solid-State Lighting of LED and Laser Diode as a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA. He and Prof Tang Zikang, director of UM’s Institute of Applied Physics and Materials Engineering, served as co-chairs of the workshop. During his time at UM, Prof Nakamura also shared with students and faculty members his vision for the future development of solid-state lighting.

Seven years later, Prof Nakamura visited UM again and gave another talk at the university as a Doctor of Science honoris causa, sharing the results of his latest research. In an interview with My UM, he noted, ‘There is a big change to UM. Everything is more than nice. When money is available and there are many good scientists, there is a good chance to make a breakthrough.’

According to Prof Nakamura, ‘At universities, abundant resources are available for young students who want to start their own company. UM is the key centre for start-ups and the students and professors should make good use of its facilities. Professors can start a company in addition to doing research with students. And then the students can learn how to start a company from them. In the future, when they are independent enough, they can start a company too.’

In June 2023, UM established the Macao Centre for Research and Development in Advanced Materials, and Prof Nakamura believes it is conducive to the advancement of technological innovation and the commercialisation of research results in the field of new materials. The centre has three research directions, namely new energy materials, environmental protection materials, and healthcare materials. Prof Nakamura also pointed out that besides helping companies stay competitive and explore new markets, it is important for the development of new materials to improve productivity and living environment, ultimately enhancing people’s sense of well-being.

Developing blue LED technology

Before 1993, scientists regarded the invention of blue LED as one of the biggest challenges of the 20th century. Despite the huge investments made in research and development by institutions and companies around the world, blue LED was elusive. With LEDs only available in red and green, people were not able to produce white light.

At the time, two kinds of materials were available to make blue LEDs, namely zinc selenide and gallium nitride (GaN). Prof Nakamura recalled that most scientists regarded zinc selenide as a promising material, resulting in more than one hundred annual papers published about this topic. In stark contrast, gallium nitride received minimal attention, with only one or two papers published on the subject each year. ‘Back in the day, people would call those who worked on gallium nitride stupid or crazy people,’ he explained.

In 1993, building on the research on p-type GaN by Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano at Nagoya University, Prof Nakamura proposed a new scientific theory and developed a technique called ‘two-flow metal-organic chemical vapour deposition’ (MOCVD). This new technique enabled the growth of high-quality gallium nitride crystals to serve as the foundation for blue LEDs, leading to a new revolution in lighting after Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb.

Prof Nakamura’s inventions have not only revolutionised the lighting industry, but also contributed to the benefit of mankind by giving rise to the bright, energy-efficient white light sources that are widely used today in the consumer and industrial sectors. As a result, Prof Nakamura, together with Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014 for the invention of the efficient blue LED.

Doing research is similar to gambling

At school, Prof Nakamura was not academically gifted. In the company, he worked very hard on his research projects but some of his co-workers believed he was wasting the company’s money. In the eyes lighting industry experts, he seemed like a fool pursuing his unorthodox research ideas. Nonetheless, fuelled by unwavering determination, Prof Nakamura firmly believed that by adhering to his vision and working at his own pace, he would ultimately develop a product that could change the world.

‘There are always hidden paths off the main road.’ Prof Nakamura has embraced this motto throughout his research career. After obtaining a master’s degree from Tokushima University in 1979, Prof Nakamura joined Nichia Corporation, a chemical company based in Tokushima, and worked in the development department. With an academic background in electrical engineering but knowing next to nothing about LEDs and engineering materials, he had to start from scratch.

For Prof Nakamura, the development of blue LED technology is not just a focus of research, but a question of profitability. The focus on profitability is also the biggest difference between research at large companies and universities. At the time, almost all large companies were using zinc selenide to develop blue LEDs. Even if Prof Nakamura succeeded in developing blue LEDs, his company might only be able to win a sliver of the pie because the market was already crowded with the major brands.

Therefore, he insisted on choosing gallium nitride as his research direction, even though his research was deemed by others a futile attempt with no promising outcome. ‘Scientists are smart, but their willingness to take risks is also important,’ Prof Nakamura said, ‘Doing research is similar to gambling. When everybody does it this way, you do it that way. Take a big bet with your time and efforts, and there will be a breakthrough.’

Modifying equipment for experiments

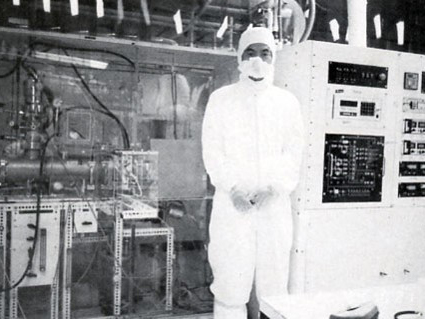

Although Prof Nakamura was enthusiastic about his research, he had no equipment budget. Instead of giving up, he rolled up his sleeves and decided to build and modify the instruments and devices needed for his research and development projects.

Prof Nakamura’s manual skills were honed at an early age. Born in 1954 in Oku, a small fishing village in Japan’s Ehime Prefecture, he grew up in an environment where resources were scarce and many villagers had migrated elsewhere. The plain village life offered nothing but sheer boredom, and young Nakamura learned how to make toys to pass the time. Such experiences also acquainted him with the fundamental principles of machinery, thus paving the way for his future career as an inventor.

Faced with limited resources at Nichia, Nakamura resorted to salvaging discarded machine parts from factories in order to construct an electric furnace. Quartz tubes, on the other hand, were essential for producing gallium phosphide. As he could not afford to buy processed quartz tubes, he had to cut, solder, and weld used quartz tubes, over and over again. Quartz welding demanded a lot of time and work, often using up one or two gas cylinders in a single day. The process sometimes reached the temperature of 2,000 degrees Celcius, which turned the laboratory into a furnace. At times, Nakamura felt more like a quartz welder than a corporate researcher.

To produce gallium phosphide, it is necessary to heat phosphorus in quartz tubes. However, when the quartz tube becomes too hot, the phosphorus vapour pressure becomes very high and eventually causes the tube to crack. As air enters the tube, oxygen reacts with the phosphorus and this may result in an explosion. Nakamura’s laboratory underwent two or three explosions every month, each emitting a loud ‘bang’ that could be heard in a parking lot a hundred metres away.

Initially, each explosion brought Nakamura’s colleagues rushing into his laboratory, which was filled with white smoke, to see if he was all right. Later, as the explosions became more frequent, Nakamura’s co-workers became so used to the noise that they no longer reacted to check on him.

During his time in Nichia’s development department, Nakamura’s daily routine involved remodelling equipment in the morning and doing reaction experiments in the afternoon. Speaking of the reason he insisted on remodelling equipment for his research, Prof Nakamura explained, ‘If we rely too much on the equipment made by one company, we would hardly develop new technologies and make breakthroughs because everyone out there can also buy and use the same equipment made by that company.’

Breaking free from common sense

Prof Nakamura also has some advice for university students. He said students should focus on coursework in the first two years to lay a good foundation of basic knowledge, and then conduct research in the remaining two years. ‘Whether you are a scientist or a researcher, you have to acquire and accumulate enough knowledge at the beginning so as to develop your own insights. Then you start doing research, get useful data through countless experiments, and gradually develop your own ideas.’

For Prof Nakamura, the ideas cited in most research papers are merely an elaboration of common sense. Only by thinking outside the box can we unlock world-changing business opportunities. ‘Instead of following in the footsteps of others, it is better to think independently and explore something that nobody else has thought of,’ he said. ‘Others may call you a fool, but don’t give up. You have to stay true to your ideas because only those innovative, original ideas have great potential for development. Scientists should aim high and develop products that will change the world. They have to persevere and be persistent in order to succeed.’

Portfolio of Prof Nakamura

Prof Shuji Nakamura holds more than 200 patents in the United States and over 300 patents in Japan. He has also published more than 830 papers in related fields. His invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources won him the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics. Prof Nakamura is a Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, a member of the National Academy of Engineering of the USA, and a member of the National Academy of Inventors of the USA. He has also received many awards.

Text: Kelvin U

Photo: Jack Ho, Editorial Board, with some provided by the interviewee

English Translation: Winky Kuan

Souce: My UM ISSUE 127