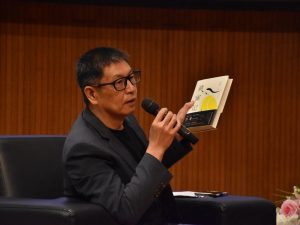

‘Earlier today I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror — an old man dressed in black, carrying a black briefcase. I couldn’t help but wonder, who is this person? He looks like an insurance agent or a computer technician that works door-to-door. Of course, it was me who was about to give a lecture on creative writing at UM’s Student Activity Centre.’

Su Tong, a renowned contemporary Chinese writer, kicked off his lecture in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities with this humorous self-introduction, eliciting a burst of laughter from the audience.

Continuing on, he said, ‘Upon closer examination, I realised that my attire wasn’t all that unusual. As we know, religious devotees dedicate their entire lives to serving God, while writers like myself spend their life in service of literature. I am essentially a wordsmith, a salesman for words, and carrying this briefcase is just another way for me to promote literature. So, there’s really nothing wrong with it, and I forgave myself for my appearance.’

Creativity begins with making things up

Yao Jingming, professor in the Department of Portuguese at UM, was the moderator of this lecture titled ‘Ways into Creative Writing’. Introducing Su Tong, he said, ‘Su Tong is a prominent figure in contemporary Chinese literature. He began his literary career in the early 1980s and wrote the renowned novel Wives and Concubines at the age of 26. Since then, he has produced numerous wise and thought-provoking novels that showcase his extraordinary fiction writing skills. Some say that writers keep the joy of writing to themselves and leave the unhappiness to the characters and readers. However, I believe Su Tong shares the suffering with the characters in his works.’

During the lecture, Su Tong mentioned a question raised by Prof Wang Qingjie from the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at an exchange activity the day before. Prof Wang asked Su Tong: ‘As a man, how are you able to describe women’s psychology so accurately and delicately in your novels?’, The writer responded with a chuckle, ‘I made up the stories in my novels as I went along.’ Prof Yao, who is also a poet and translator, added, ‘Making things up as you go along is creativity. Fiction writing requires good storytelling techniques and a lot of imagination.’

No universal criteria for evaluating literary works

In addition to being an acclaimed author, Su Tong also holds several prestigious positions, including member of the presidium of the Chinese Writers Association and distinguished professor at Beijing Normal University. His literary works, including Wives and Concubines and Petulia’s Rouge Tin, have been adapted into film and television productions. Su Tong is a recipient of the fifth Lu Xun Literary Award for his short story Arrowhead Tubers. He also received the third Man Asian Literary Prize and the ninth Mao Dun Literature Prize for two of his novels, The Boat to Redemption and Shadow of the Hunter, respectively.

Su Tong says that he finds it difficult to share his insights on creativity and writing. Since 2015, he has encountered many young students who aspire to become writers and frequently ask about how to write creatively. ‘I feel sorry for not being able to give a straightforward answer to them. Unlike science, there are no universal criteria for evaluating literary works, or right or wrong answers when it comes to creative writing,’ he said.

While there is no definitive answer, Su Tong encourages students to write their stories. ‘As the saying goes, the beginning is always the hardest. Most students are enthusiastic enough to start writing, but they don’t know where to begin. In my opinion, creative writing is a profession for geniuses and they are born with the ability to soar. For ordinary people like us, we can imitate the movements of the masters. Students can start by imitating the works of great writers such as Hemingway, Faulkner, and Poe,’ he said.

Writing is analogous to life

‘Both writing and life require finding a direction. For this reason, writing is very much analogous to life,’ said Su Tong, citing the Oedipus complex in Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence: ‘In writing, you must break free from the influence of your predecessors and escape the authority and tradition symbolised by the father figure, as it will block the door to creativity. It is impossible to jump off a giant’s shoulders, but you can pass through his crotch or armpit, and there is nothing to be ashamed of because he is your father.’

For Su Tong, breaking away from one’s father, in literary terms, means breaking free from the influences of tradition and authority. Writing is a way of bidding farewell to this father figure and searching for a new one. ‘For writers, this is a normal journey, although it may sound a bit provocative when put this way. Writing is like attempting to solve the problem of one’s father, but in reality, there are too many problems that writing needs to tackle. I don’t have a magic formula for creativity. At the end of the day, the completion of a creative work depends primarily on writing, and it requires fantastic ideas in the conception stage. This is the only way forward,’ he added.

The writer also mentioned John Cheever’s The Enormous Radio as an example of a very creative short story. ‘I often advise my students to start with small things, tiny events, when writing. If reality is compared to the ocean, then the reef is a representation of the ocean. You cannot grasp the expression and appearance of the ocean as a whole, but seagulls, reefs, beaches, and the shells washed up on shore are all touchable things. We can embrace the ocean through small things, instead of attempting to express the ocean through the ocean itself,’ he said.

AI-written texts are zombies of literary work

Su Tong also shared his views on artificial intelligence (AI) writing, which is a hot topic. At a poetry reading event held at the UM library the day before his lecture, a student asked Su Tong to analyse two poems written by Yao Feng (a pen name of Prof Yao Jingming). ‘The student told me that the two poems were written by Yao Feng in different periods. I thought one of the poems was off; the difference in quality between the two was too significant. One of them seemed to be the work of a five-year-old. I felt embarrassed and refused the student’s request. Later, the student revealed that the odd poem was actually written by AI, and I felt much relieved,’ he said exchanging a smile with Prof Yao.

‘Literary works and artworks, whether great or mediocre, possess personality, human emotions, and warmth. The inferior and mediocre quality of things written by AI is mainly due to their lack of warmth and a personal touch. I firmly believe that computers are still unable to replace us in creative writing. The precise paragraphs generated by AI are mere zombies of literary work and can never open the sacred door of literature,’ he added.

Novels provide a space outside the constraints of the law

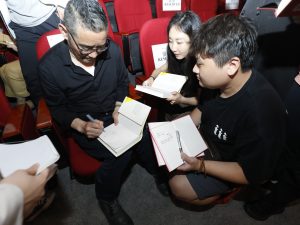

At the end of the lecture, Su Tong exchanged ideas with students in the audience who applauded his insightful remarks. Among them was a law student, who asked the writer: ‘For those of us who study law and have an ultra-practical mindset, how should we look at literature?’

‘While you are a law student, you are not confined by your identity,’ replied Su Tong. ‘The stories in novels provide a space outside the constraints of the law. Sitting next to me is Prof Yao and he is a poet. Law and poetry are the two defining pillars of human life. Law is based on reasoning, while poetry is driven by emotion and abstraction, and both are essential for human existence. It is in the interplay of these two elements that we find a truly meaningful life.’

Text / Ella Cheong, UM Reporter Li Changzhou

Photo / Ella Cheong, with some provided by the Faculty of Arts and Humanities

English Translation / Anthony Sou

Source: My UM ISSUE 124