If you suspect you are suffering from a neurocognitive disorder (NCD), you might not only need to be administered a brain scan, but also a gut examination. According to the findings of a research team at the University of Macau (UM), analysing the increase or decrease of certain microbes in the gut may help assess the risk of NCDs and neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in older people.

The Gut: The Second Brain

‘AD mainly affects the elderly, who gradually lose their ability to live independently,’ says Yuan Zhen, head of the Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences (CCBS) and professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at UM. ‘Although some drugs can alleviate the symptoms, there is still no cure for AD. As the population ages, it is likely that more and more people will suffer from AD, posing a huge challenge to global public health. Therefore, scientists have been studying the causes of the disease from different perspectives, with the “brain-gut crosstalk” being one of the focal points.’

The gut and the brain are physically and biochemically connected through a network known as the ‘gut-brain axis’, says Prof Yuan. ‘Experts refer to the gut as “the second brain” because it contains over 100 millions of neurons that send and receive signals with neurons in the brain.’ The gut microbiota, which is the ecosystem of the trillions of bacteria and other microbes in the gut, also affects the brain. For example, some metabolites, which are small molecules produced by bacteria in the gut during metabolism, can enter the brain. Previous studies show that some of these metabolites can cause NCDs.

Imbalance of Gut Microbiota Affects the Brain

‘A healthy gut is characterised by the diversity of microbial species, but the diversity of gut microbiota decreases with age. During this process, the proportion of pathogenic bacteria usually increases, causing an imbalance,’ says Zhao Yonghua, assistant professor in the Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences at UM. The research team of Prof Zhao, who is also interim associate head of the Macau Institute for Translational Medicine and Innovation and a registered Chinese medicine doctor, believes that the imbalance in the gut is related to NCDs, and the team has found new evidence to support this hypothesis.

Analysis of Gut Microbiota

In 2019, Prof Zhao’s team launched a correlated study on the differentiation between Chinese medical ‘Constitution-Disease-Syndrome’ and the characteristics of gut microbiota and metabolomics in the elderly with cognitive dysfunction in Macao. Part of the project was conducted in collaboration with experts from Kiang Wu Nursing College of Macau, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University, and Shenzhen People’s Hospital.

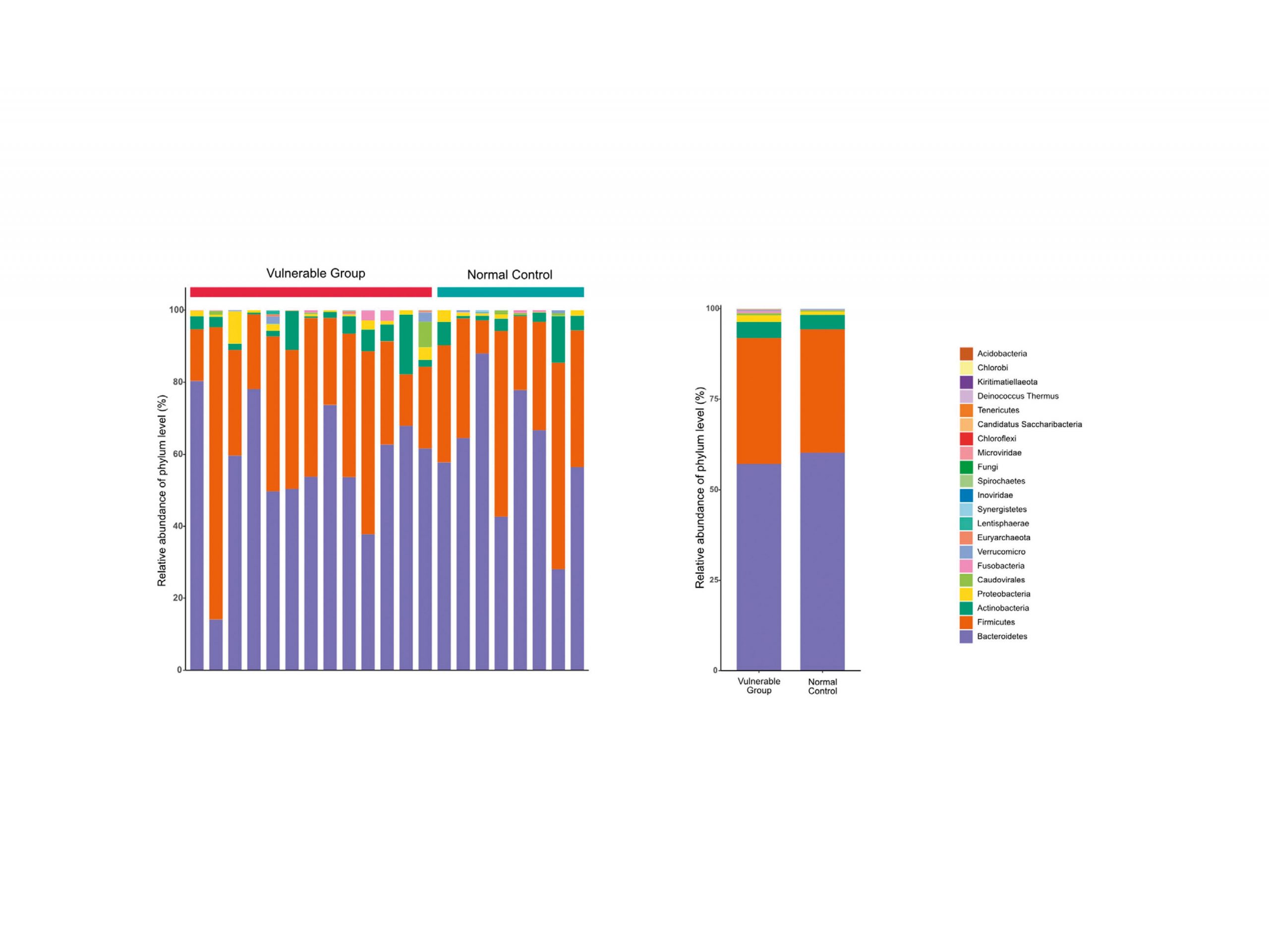

After recruiting 400 elderly residents in Macao in 2019, 21 participants with normal cognitive function were selected through a rigorous matching of education levels, lifestyles, and chronic diseases. Eight of them were classified as the ‘control group’ with a balanced Chinese medicine constitution, while 13 were classified as the ‘vulnerable group’ with a Yin deficiency constitution, which is prone to NCDs. The team collected the faeces and urine of the elderly and ran a test to determine their ‘neurocognitive scores’ in areas such as memory, attention, and language. These steps were repeated with the same participants in 2021.

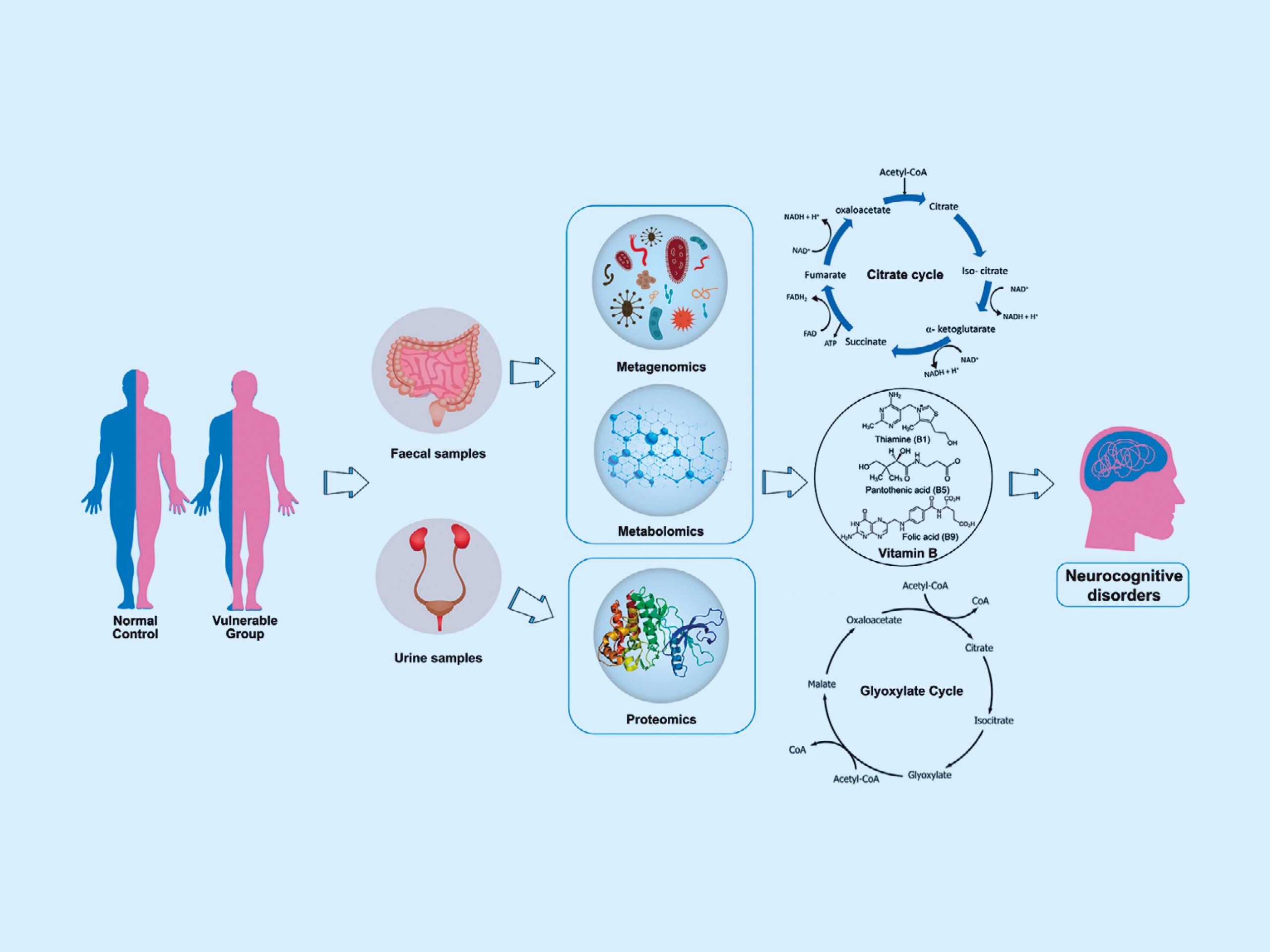

To determine the differences in the microbiota and metabolites in the excreta of two groups of participants in 2019, the researchers conducted a multi-omics analysis assessing different types of data, including metagenomics, metabolomics, and proteomics. They found that the neurocognitive scores of each person in the control group did not change much. However, most participants in the vulnerable group presented a significant decline in their scores, with signs of further deterioration in their cognitive function. In addition, three members in the vulnerable group developed mild NCD, suggesting that NCDs are more likely to occur in Yin-deficient older people with certain gut bacterial and metabolic characteristics.

Moreover, the increase in Ruminococcus gnavus, Lachnospira eligens, Escherichia coli, and Desulfovibrio piger was significantly higher in the faeces of the vulnerable group than that in the control group. ‘This suggests a possible negative impact of these bacteria on cognitive functions,’ says Prof Zhao. He adds that the two groups showed significant differences in the levels of glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism and vitamins B in the faecal metabolites, as well as in the levels of expression of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 (eIF2α) and amine oxidase A (MAO-A) in the urine exosomes.

Assessing the Risk of NCDs

The findings of Prof Zhao suggest that it may be possible to assess the risk for developing NCDs among the elderly by examining multi-omics characteristics of bacteria in their gut, vitamin B digestion and absorption, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, so that early intervention could be planned. In the next phase of the research project, the team may recruit more elderly people to find out whether changes in the gut microbiota ecological environment can exert a satisfactory therapeutic effect on NCDs.

‘All disease begins in the gut,’ said Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician known as the ‘Father of Medicine’. ‘While we aren’t sure of the exact pathway by which changes in the gut lead to NCDs, our gut and brain are definitely much more closely “crosstalked” than many have thought,’ says Prof Zhao. ‘A healthy gut not only helps with digestion, but also benefits the whole body, including the brain.’

Chinese & English Text / Davis Ip

Photo / Jack Ho, with some provided by the interviewee

Source: UMagazine ISSUE 26

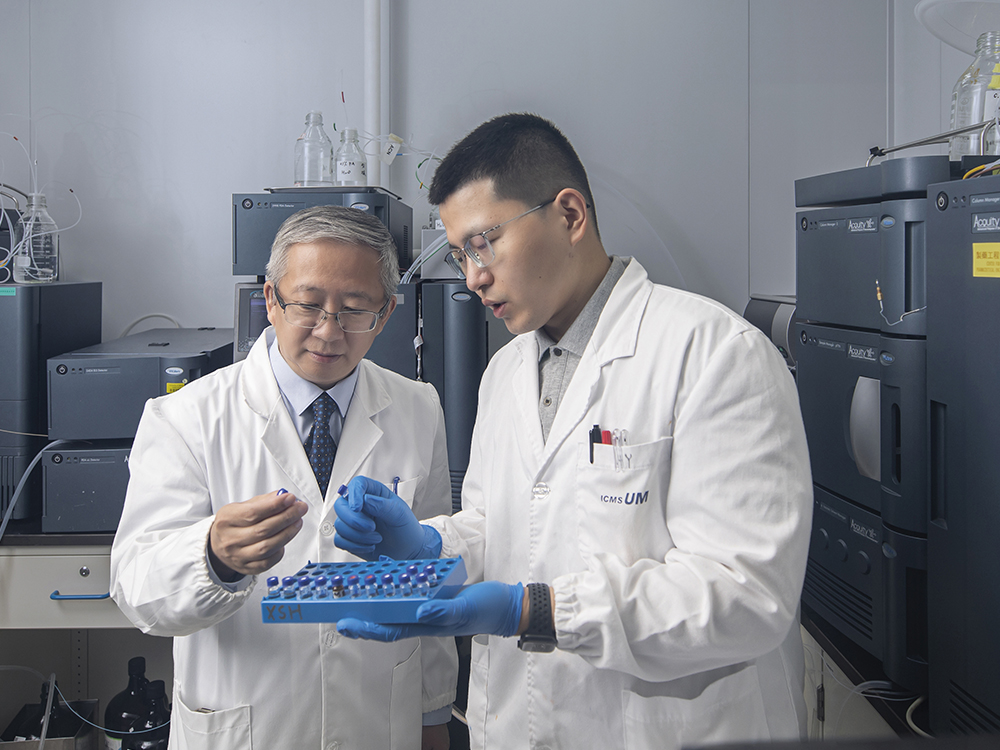

Prof Zhao Yonghua’s team analyses the gut microbiota of the elderly by using macrogenomic, metabolomic and proteomic data.

Prof Yuan Zhen

Prof Zhao Yonghua

Prof Zhao Yonghua (left) and PhD student Han Yan

Proportions of different microorganisms at the genus level in the gut microbiota of the elderly in the vulnerable group and the control group