To ordinary people, a cowrie shell is merely the hard protective outer layer of a marine mollusc. But in the eyes of historian Yang Bin, this small, unassuming sea shell can provide a glimpse into a piece of global history that not many people know of.

3,000-Year-Old Cowrie Shells

Yang Bin is head of the Department of History of the University of Macau (UM). In his office, one can find antiques that he has collected from around the world. They include bronze cowries from the Shang dynasty and porcelain, calligraphy works, and paintings from different eras. Among these collectables, the cowrie shells displayed on a celadon plate are the most inconspicuous, but also the oldest — they are 3,000 years old.

At the beginning of the interview, Prof Yang handed us the cowrie shells so that we could observe them closely. Pearl white in colour and of similar size, the shells have a long ‘teeth mark’ on the surface and are slightly convex on the back. ‘I have been studying these cowrie shells for 18 years. These shells are valuable antiques from thousands of years ago. They played a critical role in the ancient trade market and were of significant value to global trade,’ says Prof Yang.

In his book Cowrie Shells and Cowrie Money: A Global History, published in 2021, Prof Yang explores the origins, evolution, and values of cowrie money from the perspective of global history. By bridging the gap between Chinese history and world history, Prof Yang paints a vast picture of monetary history with both local and global characteristics.

The book analyses cowrie shells and cowrie/shell money used in India, Southeast Asia, pre-Qin China, ancient Yunnan, west Africa, the Pacific islands, and North America from the Neolithic period to the mid-20th century. The book makes breakthroughs in economic history, monetary history, maritime history, and world history, and was ranked among the ‘Top Ten Books of 2021’ by Social Sciences Academic Press (China), the ‘Top 20 History Books of 2021’ by China Reading Weekly, the ‘Recommended Books of 2021’ by The Beijing News, and ‘Recommended Books’ by the 17th Wenjin Book Award of the National Library of China. ‘Of the more than 250 species of cowries, only Monetaria moneta, commonly known as “money cowry”, and a small number of Monetaria annulus, commonly known as “ring cowrie”, were selected to be cowrie money,’ says Prof Yang. ‘When the cowries are fully grown, their shells are of similar size, about 1.5 to 2 cm in length and 0.8 cm in width, as if they are manufactured in assembly lines, which is also the main reason why they became currency in India and West Africa. Moreover, weighing only about 1 gram each, the cowrie shells are light, portable, and difficult to break. They can be easily weighed, measured, and counted, making them an excellent choice as a medium of exchange for small transactions.’

A Sea Shell Linking Chinese History and World History

Born in Zhejiang province, Prof Yang completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the Renmin University of China in the 1990s and his PhD at Northeastern University in Boston in 2004. He taught at the Renmin University of China and the National University of Singapore before joining UM in 2017, and he became the head of the Department of History in July 2021. Prof Yang is passionate about the study of Chinese history, global history, maritime history, and the history of science and medicine. He is also the only member of the Xiling Seal Art Society at UM.

As one of the first scholars to advocate studying China from its border areas, Prof Yang began to study the history of Yunnan province during his doctoral studies, and chose it as the topic of his doctoral thesis. During his fieldwork in Yunnan, Prof Yang learned about the use of cowrie money in inland Yunnan in ancient times. He then told his supervisor about his findings upon returning to the United States. ‘My supervisor mentioned to me the history of cowrie money in West Africa and it provoked my interest in studying cowrie money. Later, I began to conduct in-depth studies on this topic and wrote three articles about the rise and fall of cowrie money in Yunnan, Yinxu, and Asia, respectively,’ says Prof Yang. ‘I thought I had put all my points in the articles, but then I made so many new discoveries that I wrote another book, Cowrie Shells and Cowrie Money: A Global History, to analyse them in detail.’

While most scholars separate Chinese history from world history, Prof Yang hopes to provide a link between the two disciplines: ‘China is within the world, not outside of it,’ he says. Prof Yang’s book begins with the first use of cowrie shells as currency in the Maldives before chronologically analysing the circulation of cowrie money in different regions. Supported by archaeological records, travelogues, and codices from around the world, the book highlights the inter-regional connections, developments, and contexts of cowry money in order to tell a global story from local perspectives.

In addition, Prof Yang presents a different perspective from that of many scholars in his book, which he considers one of the highlights. ‘While many scholars in academia in China consider cowrie shells as the earliest money in China and China as the first country to use cowrie shells as currency, I point out that cowrie shells were only a “money candidate” in ancient China, but not a currency. “Money candidate” refers to items with the potential to be used as currency, including items that did not really become currency,’ says Prof Yang. ‘Previously, people did not distinguish between valuables and currency, thinking currency was equivalent to wealth and something of value. Cowrie shells came from the remote Indian Ocean, so they were difficult to transport and the supply was unstable. For this reason, they did not become currency in ancient China.’ He also compares cowrie shells in ancient China to diamonds: ‘Although diamonds can be exchanged for money, people did not use them for consumption. In the same sense, cowrie shells did not become currency in ancient China.’

Historical Encounter with Macao

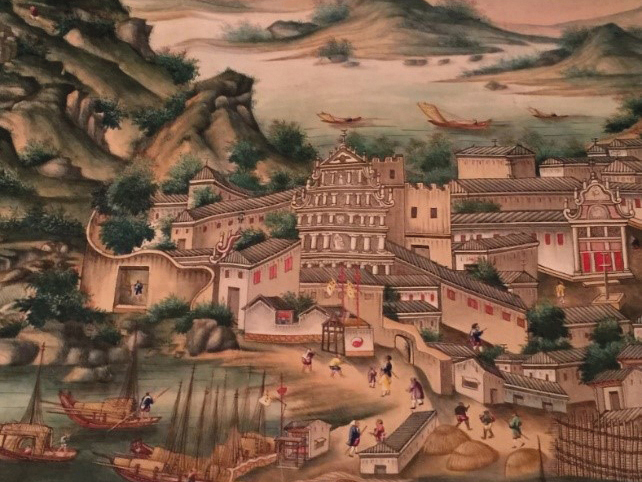

In spring of 2017, Prof Yang was in Singapore, writing a book about the sinology master Prof Jao Tsung-I’s experiences as a faculty member at the University of Singapore. During the data collection process, he came across a 318 cm long, 30 cm wide landscape scroll of Macao from the Qing dynasty on display as part of the Lee Kong Chian Collection in the National University of Singapore Museum. Prof Yang identified the scroll, which was not included in any Macao map collections or paintings. It is the largest existing Chinese landscape painting of the topography, scenery, and dwellings of Macao.

At that time, Prof Yang had never studied the history of Macao. The fateful encounter with the painting occurred just before he began working at UM, which presented him a unique opportunity to form a relationship with Macao.

‘I was determined to study what was painted in this landscape scroll with bright colours and grandeur,’ says Prof Yang, who has walked almost every hill and street in Macao in the years since his arrival, generally confirming the topography of Macao as drawn on the map. Taking into consideration the literature from the same period and having conducted a comparative analysis of the painting’s subject matter, content, and characteristics, Prof Yang has concluded that this traditional landscape scroll was painted by a Chinese artist influenced by Western painting methods and dated the painting to around the early or mid-Qianlong period (mid-18th century). In addition to being the largest known topographical painting of Macao, the landscape scroll is also the largest and the earliest traditional Chinese landscape painting of Macao from a Chinese perspective, which vividly depicts the well-being of both Chinese and foreigners in Macao living in a ‘golden age’ under the sovereignty and governance of the Qing dynasty. Prof Yang later presented this discovery in his article titled ‘“A Hundred Miles of Rivers and Mountains” — A First Look at a Newly Discovered Macao Landscape Scroll from Singapore.’ The article was published in the Chinese edition of Review of Culture, a journal produced by the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macao and edited by UM’s Centre for Macau Studies. ‘Inspired by the landscape scroll, I am going to write a book about Macao’s image in the 18th century from various perspectives,’ he says.

Finding Pleasure in History Research

Recounting his experiences of learning and researching history, Prof Yang says that it was purely by chance that he started to study history when he was young and he went overseas to pursue further studies both because of the times and because of his aspirations. ‘I find it a pleasure to conduct research in history. Even after all these years, I still get very excited when I find pieces of evidence that can prove my point of view,’ says Prof Yang. ‘I believe the ultimate goal of life is to enjoy oneself, and this is what drives me to do research in history.’

Source: UMagazine ISSUE 26

Prof Yang Bin and his many collectables in his office

Cowrie Shells and Cowrie Money: A Global History by Prof Yang Bin

Cowrie shells that connect Chinese history with world history

Prof Yang Bin gives a talk titled ‘“Treasured Shells” from the Indian Ocean: Cowries in Early China’

A landscape scroll of Macao from the Qing dynasty in the National University of Singapore