China is building a global network of partnerships as instruments to advance institutional and multilateral cooperation. As President Xi Jinping emphasised during his 2023 New Year address, ‘today’s China is a country closely linked with the world’. Since the establishment of its first strategic partnership with Brazil in 1993, China has not only engaged in more bilateral commitments, but has also strengthened existing ones into more comprehensive forms of cooperation.

Flexible and Consensus-Driven Partnerships

Chinese partnerships are in significant ways distinct from classical, conventional alliances, as China’s approach to foreign relations is heavily influenced by traditional Chinese culture and the landmark notion of non-alignment, with relationality as a guiding principle. Whereas classical alliances that once prevailed in international relations tend to be driven by military and/or hostile intents and necessitate some level of ideological and/or political alignment among the multiple states involved, China builds bilateral partnerships that are premised on equality, mutual respect (especially on the importance of political independence), mutual benefits and harmonious development; non-antagonistic and characterised by non-alignment; and consensus-driven. Max Weber defined consensus as ‘something that exists when our expectations regarding the behaviour of others are realistic’, and it is through consensus that partnerships turn such expectations into reality.

Chinese partnerships serve as ad hoc, dynamic, consensual and non-legally binding political-diplomatic instruments designed to set a flexible, bilateral and pragmatic cooperation framework. Their aim is to advance stable sovereign interests and generate a reasonable level of mutual benefits, economic security and peaceful development. Indeed, they are political cooperative frameworks and models of tailor-made cooperation that can translate different forms of consensus into ‘a wide vision for change’ and achieve ‘common points […] through understanding and negotiations’. They can be as elastic, adaptable and dynamic as the two sides wish them to be, especially in comparison with traditional, conventional alliances.

For example, the number of projects within a partnership can increase or decrease; the overall scope, nature, and terms of cooperation can be modified; and the implementation process can accelerate, decelerate or even be paused to better cater to the individual parties’ national interests and/or domestic policies and priorities. Such flexibility allows Chinese partnerships to accommodate and facilitate a variety of constituent programmes, providing a versatile basis for the two parties to continue to achieve substantive cooperation. Such flexibility also means that no partnerships exactly replicate others, as each is unique to the specific implementors.

For China, these partnerships provide a stable, balanced platform for expanding and coordinating its interests with other countries, shaping ‘an international environment that is propitious to its rise as a global power’, as well as becoming a significant international actor and advancing its global vision—to build communities with a shared future for humankind.

China’s Strengthening Ties with Portuguese-Speaking Countries

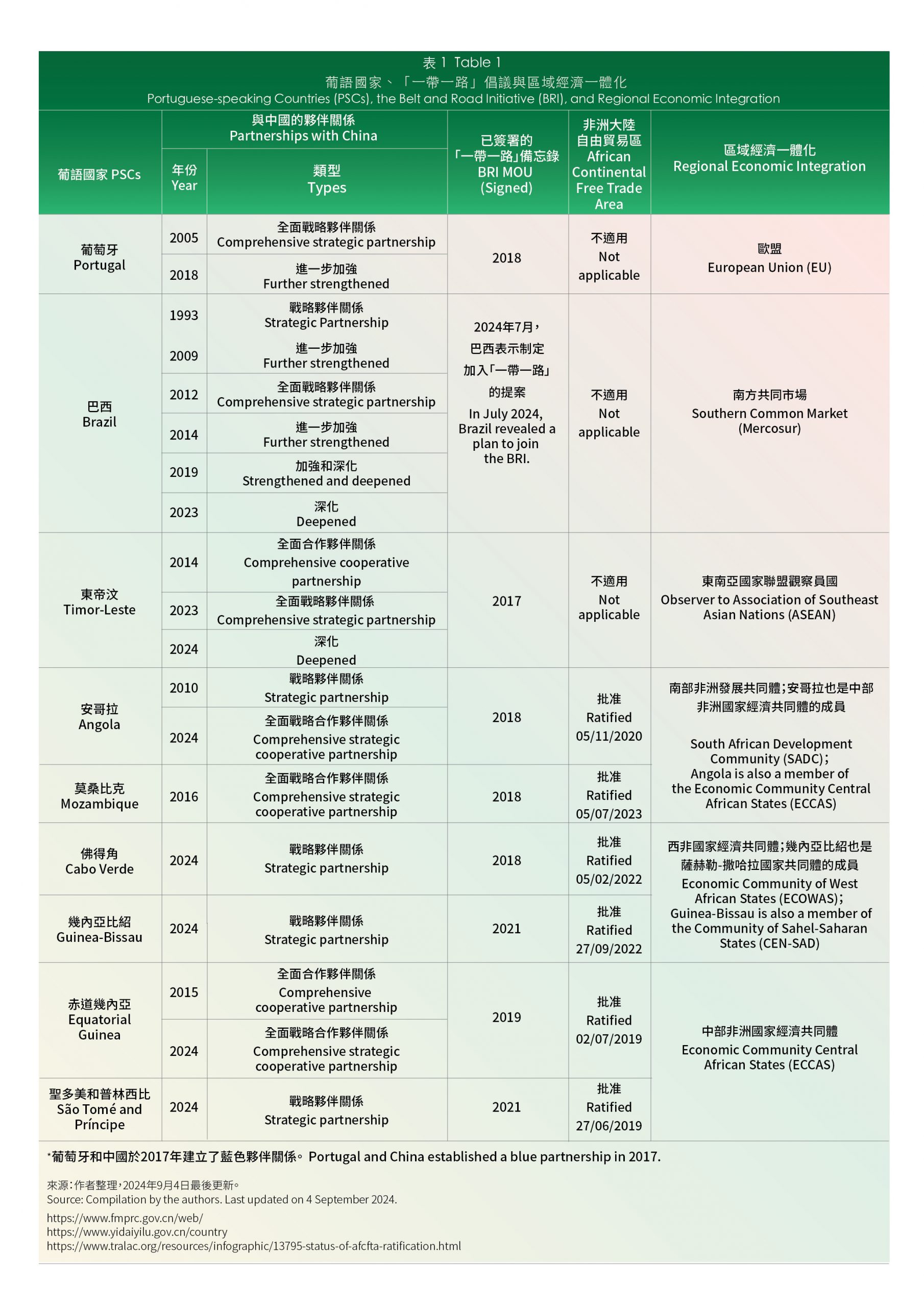

Among all Chinese partnerships, less than 10 per cent are not designated as ’strategic’. Meanwhile, the presence of other descriptors such as ‘comprehensive’, ‘cooperative’, ‘all-weather’, ‘all-round’ and ‘friendly’ indicates the scope of cooperation and/or bilateral relations. China and Portuguese-speaking countries have been consistently reinforcing their mutual relations through partnerships. Table 1 depicts the dynamics associated with the establishment and advancement of partnerships between China and the nine Portuguese-speaking countries and their incorporation in regional economic spaces.

Up to 2024, all Portuguese-speaking countries have established partnerships with China, and all have reached the ‘strategic’ level, underscoring the importance of these partnerships. Over the past two years (2023 and 2024), China’s partnerships with most Portuguese-speaking countries have significantly improved, especially with Timor-Leste and African Portuguese-speaking countries, facilitating bilateral flows of cooperation and regional integration, namely through access to new markets and production centres.

Economic Integration Through Partnerships

Chinese partnerships, which are tailor-made cooperation models operating individually or in conjunction with the Belt and Road Initiative, not only contribute to the national development plans of each of the Portuguese-speaking countries, but they also function as mechanisms of economic integration, strengthening their regional role. International relations have never been static, and any bilateral relationships (including partnerships) will evolve. Therefore, these partnerships remain essential diplomatic instruments between China and Portuguese-speaking countries. Side-by-side to the continuing development of bilateral relations between Portugal, Brazil, Timor-Leste and China, the 2024 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) represents the inception of a new era of modernisation in the context of South-South cooperation. Indeed, the 2024 Beijing Summit of FOCAC has reinforced the value of Chinese partnerships as a political-diplomatic instrument as they represent a consensual, pragmatic and cooperative framework for developing a win-win, mutually beneficial relationship. Notably, China’s strategic direction is to eventually establish a community of shared future with every country and region.

Authors:

Francisco José Leandro is an associate professor with Habilitation in International Relations in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Macau, and deputy director of the Institute for Global and Public Affairs in the faculty. He received a PhD in Political Science and International Relations from the Catholic University of Portugal in 2010.

Li Yichao is an assistant research fellow at the Institute of African Studies at Zhejiang Normal University. She received her PhD from the Institute for Research on Portuguese-speaking Countries at the City University of Macau in 2021. She also received a Master of Law in Chinese Language – Comparative Civil Law from the University of Macau in 2018. From 2021 to 2022, she was a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for International Studies, ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal.

Text / Francisco José Leandro, Li Yichao

Chinese Translation / Davis Ip

Portuguese Translation / Editorial Board, UM Reporter Celia Wang Chuyue

Source: UMagazine ISSUE 30