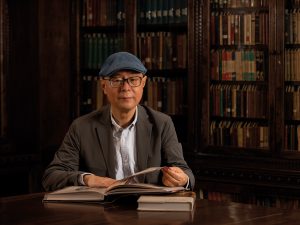

The enigmatic smile of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has long captivated audiences. To Prof Li Jun, head of the Department of Arts and Design at the University of Macau (UM), Renaissance artists’ genius goes beyond their technical skills. Their works capture the socio-cultural currents of their times, offering deep insights into human emotions and inner conflicts. This, Prof Li believes, is the true value of art, and is what fuels his passion for the study of art history.

Unveiling the Artist Within

After graduating from Peking University, Prof Li taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts for 37 years. He also served as dean of the School of Humanities. His research interests encompass Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance, transcultural arts, cultural heritage, exhibition planning, as well as visual culture and art history methodology. Among his notable publications are A Visible History of Art: From Church to Museum, and A Transcultural History of Art: On Images and Its Doubles. In June 2023, he joined UM’s Department of Arts and Design. He is currently working with other professors in the department to nurture the next generation of artists and art historians.

Prof Li believes that art is an ideal world crafted by our heart and hands. ‘Children are naturally drawn to scribbling, even before they develop their writing skills,’ he explains. ‘This innate connection underlines human’s instinct to understand the surrounding world. For example, a child who just starts learning to draw may draw a circle, which can be seen as creating a separation from the outside world. In other words, drawing is a way to express one’s worldview. I am convinced that art is not merely an expertise; it is intrinsically linked to personal growth,’ he says.

Born in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, Prof Li has had a passion for painting, poetry, and literature since a young age. In 1980, as mainland China began its reform and opening-up, he enrolled in the Department of Journalism of the Beijing Broadcasting Institute (now known as the Communication University of China), hoping to pursue a literary career. He regarded the study of aesthetics as integral to the intellectual renaissance of the time and immersed himself in reading publications on aesthetics and philosophy. In 1984, he furthered his studies by enrolling in a postgraduate programme in aesthetics at Peking University’s Department of Philosophy.

Under the guidance of Prof Ge Lu at Peking University, Li focused on Chinese aesthetics in his studies. During that time, there was an influx of Western ideas into China, prompting intellectuals to reassess the core of Chinese culture. This setting had a profound influence on Prof Li’s art criticism and his research on Chinese art theory. He explains, ‘My approach to art is to fully understand Western art concepts and then revisit our own traditional culture based on that.’

Exploring the Mysteries of Renaissance Art

During his professorship at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Prof Li gained a profound understanding of European art through several academic visits. He visited the National Heritage Institute in France in 2002, the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne in 2003, and Harvard University in the US in 2011. ‘Art is woven into the fabric of everyday life in Europe,’ he remarks. ‘Art pieces are omnipresent in churches, museums, and beyond, presenting abundant opportunities for individuals to step into the minds of great artists. I could immerse myself in the realm of art at any given moment, wherever I went.’

Proficient in Chinese, English, French, and Italian, Prof Li believes that mastering multiple languages is essential for in-depth study of art history. ‘It is necessary to immerse oneself in the original works, the source texts, and the authentic language environment,’ he says. ‘The source language serves as the cultural language of the creators. Without understanding the creator’s cultural language, we can hardly get a grasp on their works and truly appreciate them.’

Prof Li believes that some artworks can stand the test of time because they carry profound meanings. To understand what message the artists sought to convey through the masterpieces, one must understand their historical backdrop. Prof Li, who advocates studying the history of Renaissance art through source texts, notes, ‘In his painting Annunciation, the 15th-century artist Francesco del Cossa painted a column between an angel and the Virgin Mary. The column was surprisingly arranged, which leads to a question: do the angel and Mary really see each other? However, from a macroscopic perspective, the presence of the column underscores the interplay of the divine in the secular world. The column symbolises Christ, and Christ himself is a miracle.’

Prof Li points out that Renaissance artists often had to seek a compromise between the sacred and the secular in their works. ‘From a modern perspective, that era embraced both humanism and faith, sometimes resulting in seemingly paradoxical artistic representations. To decode these, we have to immerse ourselves in the artists’ religious mindset.’

Enchanted by Leonardo da Vinci’s Works

Among the renowned works of the Renaissance, none is more celebrated than Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, which is housed at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Prof Li is fond of Leonardo da Vinci and dedicates a significant portion of his office bookshelf to the Renaissance master. ‘The fascination of his artworks lies in their myriad hidden layers, which always captivate those who seek to decipher them.’

Prior to Leonardo da Vinci, Western female portraits were often depicted in profile, similar to the portrait on a coin, with the silhouette of the figure highlighted. However, the Mona Lisa presents a three-quarter profile. Prof Li explains that when Leonardo da Vinci painted this masterpiece, he employed his signature sfumato technique. The artist created a gradient effect on the painting by applying successive thin layers of semi-transparent paint and letting each layer dry before adding the next. This technique gives the impression that the figure in the painting is gazing at the viewer, regardless of their position.

According to Prof Li, the brilliance of the Mona Lisa extends beyond the groundbreaking technique; it lies in the emotional connection the painting establishes with the viewer. ‘Leonardo da Vinci’s body of work depicts interpersonal relationships. His early pieces demonstrate the relationships between the figures within the painting, while his later works focus more on the interaction between the painting and the viewer. When we look at the Mona Lisa, we all become, in a sense, Leonardo da Vinci. We not only observe the smiling lady and the landscape behind her, but may also sense an emotional connection with the lady, who symbolises a mother figure. The underlying meanings of these masterpieces often transcend the artworks themselves and become a narrative that involves the viewer.’

The Representation of Life in Art

For Prof Li, art is a harmonising force amid diverse perspectives, going beyond any kind of dominance or binary opposition. ‘In the field of art, each piece of work is a “representation” that signifies the artist’s endeavour to reconstruct and reconceptualise the world they perceive,’ he explains. ‘For me, art is a re-presentation of life. It is a common desire for humans to experience life anew. Art bridges the gap between reality and ideals, and is the very medium through which we depict our ideal world.’

Prof Li believes that everyday life is entangled with contradictions, such as the tug-of-war between self-consciousness and the unconscious mind. ‘Against this backdrop, the true value of art lies not in eradicating the abnormalities in life but in orchestrating a delicate balance of the contrasting forces within a single artwork,’ he says. ‘Therefore, art is more of an imagined resolution rather than a direct solution to various conflicts. Through the representation of the conflicts, art allows people to perceive one another’s emotions and thoughts in an inclusive and compromising manner.’

Multiculturalism Inspiring Artistic Creation

Prof Li, who first set foot in Macao in 2020, has a unique affection for the city. One of the reasons is that Macao resembles the European cities with which he is familiar, where there are no clear boundaries between old and modern buildings. For instance, the Na Tcha Temple sits right next to the Ruins of St Paul’s, which is neighboured by residential buildings. This kind of urban landscape is rare in mainland China. ‘Driving around the Macao Peninsula, Taipa, and Coloane, one can see how the scenery changes from bustling modern neighbourhoods to the historic district, from the glittering Cotai Strip to the serene allure of Coloane. And, as you reach the UM campus, it feels like stepping into a peaceful paradise. It is genuinely mesmerising how every turn reveals a different scenery,’ he says.

Prof Li served as academic advisor to the exhibition ‘From Courbet, Corot to Impressionism—The World of Light and Shadow from Normandy, France’ held in Beijing in 2021. He is now planning to bring this exhibition to UM in 2024. The exhibition will feature a selection of works by renowned French Impressionists such as Monet and Boudin, alongside celebrated artists from the realms of French Realism and the Barbizon school such as Courbet and Corot. The selected pieces will mainly include seascape paintings of Normandy in France. In addition, Prof Li wants to introduce a Macao-themed session titled ‘Beyond the Sea’, showcasing works by artists from Macao.

Looking ahead, Prof Li hopes to incorporate Macao’s unique history into UM’s art programmes and seek more resources for student creative endeavours. He says, ‘In UM’s Department of Arts and Design, an environment that fosters multimedia and interdisciplinary art learning and research, our goal is to nurture contemporary artists who excel in integrating Chinese and Western, ancient and contemporary cultures, and possess the ability to work across diverse mediums. In doing so, we strive to connect Macao’s arts with the global community.’

Chinese & English Text / Debby Seng, UM Reporter Li Changzhou

Photo / Jack Ho, with some provided by the interviewee

Source: UMagazine ISSUE 28

Prof Li Jun

The Mona Lisa on display at the Louvre Museum

A Visible History of Art: From Church to Museum, A Transcultural History of Art: On Images and Its Doubles, and Finding A Homeland at the End of the World – The Trans-cultural Exch

Prof Li Jun

Prof Li Jun was academic advisor to the exhibition ‘From Courbet, Corot to Impressionism—The World of Light and Shadow from Normandy, France’ held in Beijing in 2021. (Credit: Webs