Words are powerful. Encouraging words can go a long way towards

helping someone achieve his full potential, while hurtful words can leave people

traumatised for life. How can we be more careful about what we say in a conversation?

Learn to Control Your Emotions

We have all been at the receiving end of verbal attacks in our

lives. To Dr Liang Qingning, a resident fellow of Ma Man Kei and Lo Pak Sam

College, the most hurtful words are those that deny his contribution to a

project when he has done his best. A few years ago, Dr Liang and his friends

co-organised a grand charity gala dinner on a tight schedule. They encountered many

unexpected difficulties in the process, but the event was a great success and the

participants enjoyed it very much. However, when the organisers were celebrating

after the event, a donor friend who did not participate in the preparation

said: ‘I don’t think you put your heart and soul into the event, and I

personally found many flaws in the arrangement. This left Dr Liang feeling very

upset.

‘At that time, I thought my friend was being picky and wanted to

deny our contributions,’ says Dr Liang. Although unhappy about what he heard, Dr Liang did not confront his friend

right away. He calmed himself first, and later found an opportunity to ask his

friend about the things he thought the organisers could have done better. Dr

Liang then told the friend about the details of the various arrangements and

the reasons for those arrangements. ‘After I explained everything, he began to

show appreciation of our work and apologized for what he said,’ says Dr Liang.

From this incident, Dr Liang learned the importance of emotional intelligence. He

realised that in order to clear up a misunderstanding, one must refrain from knee-jerk reactions, and learn to think positively and

initiate timely and effective communication with the other person. Dr Liang likes to share tips for effective

communication with his students. ‘Our residential college is like a second home

for our students. Here, students from different backgrounds live under the same

roof,’ says Dr Liang, ‘So they must learn how to be respectful and understanding

when communicating with each other.’

Words Can Hurt

‘It’s none of your business!’ It has been several years after the

unpleasant exchange happened. But Fortuno Hong, a first-year student from the Faculty of Education, still feels

stung by his friend’s words.

He never thought a close friend of his would say that to him. As he recalls, on

the day of the incident, this friend lay his head on the desk and was unusually

quiet. ‘He was not his usual self, as if he was worried about something,’ says

Hong. ‘Although he is a quiet person, he likes to share his feelings with me. I

thought we were close friends.’ So he approached his friend and asked: ‘What’s

wrong?’ ‘It’s none of your business!’ his friend huffed. Feeling embarrassed at

being shouted at in front of other students, Hong turned red and said:

‘Alright’ and then left.

The next day, Hong went to find his friend. Neither of them

brought up the incident. They both pretended it never happened. But Hong

actually felt awful after the incident and couldn’t even concentrate on his

homework. He said at that time he was still a high school student and was

probably more sensitive than the average boy. Hong never again asked the friend

what happened to put him in such a foul mood that day. Later he found out from

others that his friend was scolded by a teacher because of his homework. Luckily, this incident did not break their friendship and they remain friends

to this day. But sometimes Hong feels the urge to ask this friend: ‘Do you know

what you said that day hurt my feelings?’

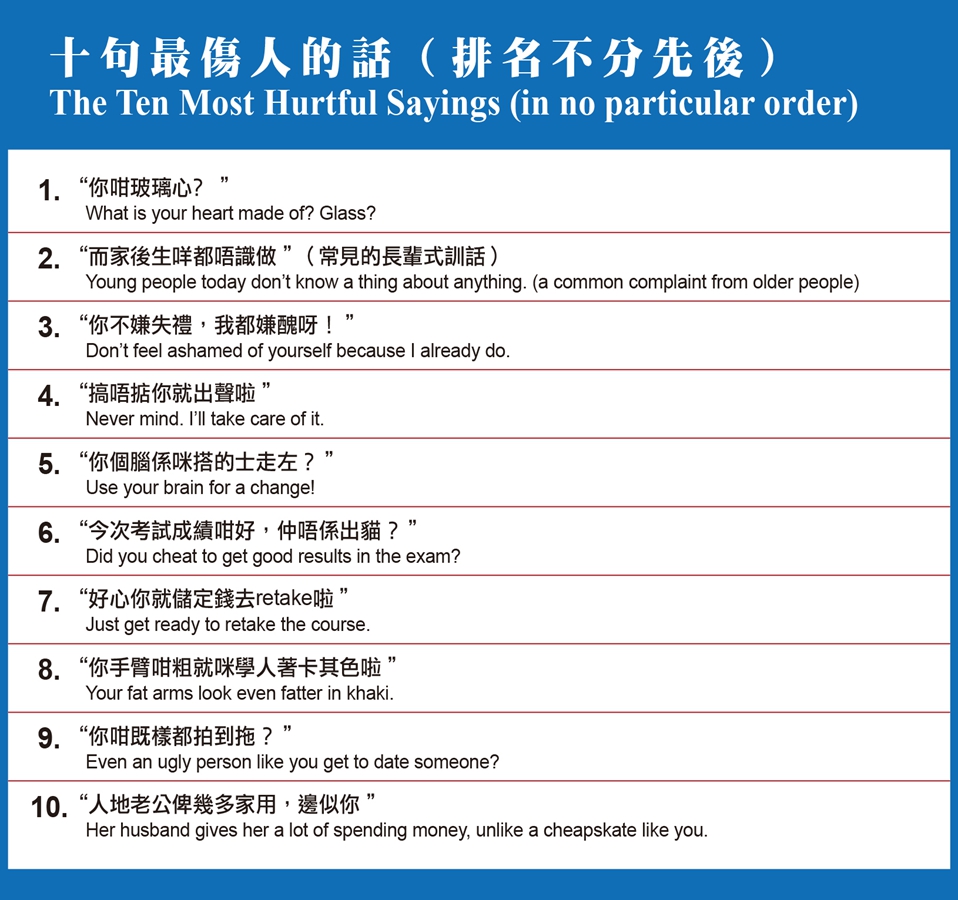

Break the Vicious Cycle

Li De, associate dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and a

professor from the Department of Sociology, says that the prevalence of verbal

abuse has its roots in the family environments in the Chinese communities. ‘Many Chinese parents today still adopt an

authoritarian parenting style. For example, they would scold their children

when they don’t behave,’ says Prof Li. ‘Sometimes they use threat (‘No food until

after you do what I tell you to’) or ridicule (‘Stop acting so stupid!’),

without regard for their children’s feelings.’ Prof Li adds that this kind of

parenting style teaches children to inflict verbal abuse by osmosis, because it

makes them think it is alright to get what they what by using verbal abuse or

to entertain themselves by ridiculing others. In other words, children who were

once the victims of verbal abuse are likely to become perpetrators when they grow up, and many of

them will have difficulty getting along with others. Prof Li have also seen

some students hurling insults at each other childishly simply because their

feelings were hurt. In order to break this vicious cycle, Prof Li suggests that

we should be more aware of the destructive nature of words that are used to

scold, intimidate, and ridicule. This is particularly important for parents, as

hurtful words can cause immeasurable damage to children. He adds that parents

should be more careful about what they say and how they act in front of

children. Finally, Prof Li suggests that students who have been verbally abused

should take general education courses in family relations, gender relations, and

mental health, in order to heal their wounds.